Every woman should have access to potentially life-saving screening

Cervical cancer screening has dramatically reduced new cases and deaths from the disease over the past 50 years.1 But the number of women in the US who are overdue for cervical cancer screening has been growing.

~4.5M

fewer women were screened for cervical cancer between 2019 and 20232

>25%

of women are not up to date with their screening

60%

of women diagnosed with cervical cancer had not received appropriate

screening in the 5 years prior to their diagnosis 4

In many cases, noncompliance with screening guidelines can be attributed to lack of knowledge or access to appropriate care. There are also some women who delay testing because of the invasive nature of speculum-based specimen collection.

These may include:

- Transgender individuals5

- Women with religious barriers to such procedures6

- Women with a history of physical trauma7

Testing from Quest supports leading cervical cancer screening guidelines, including from the

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology8

- US Preventive Services Task Force9

- American Cancer Society10

Learn more about our screening solutions. Download brochure

Reducing barriers to testing

Our comprehensive array of screening options is designed to reduce barriers and empower you to tailor testing approaches to meet the unique needs of each patient.

Co-testing with Pap and HPV

Primary HPV screening physician-collected

HPV screening patient self-collected

High-risk HPV (hrHPV) causes virtually all cervical cancers11

HPV testing is recognized as providing the most clinically useful results for detecting cervical cancer risk in its earliest stages when treatment is likely to have the greatest impact.

Uncovering high-risk HPV strains across testing modalities

Pap testing

We provide robust cytology testing and reporting to meet your cervical cancer screening needs.

- Almost 1 in 5 Pap tests are reviewed a second time as part of routine quality control

- Our quality control standards meet and often exceed all state and federal requirements

- Our team of medical experts includes 450 anatomic and clinical pathologists—a significant number of whom have a gynecologic subspecialty—who meet frequently to discuss your most challenging cases

- We perform a higher volume of Pap and high-grade lesion evaluations than most other labs

HPV and Pap co-test

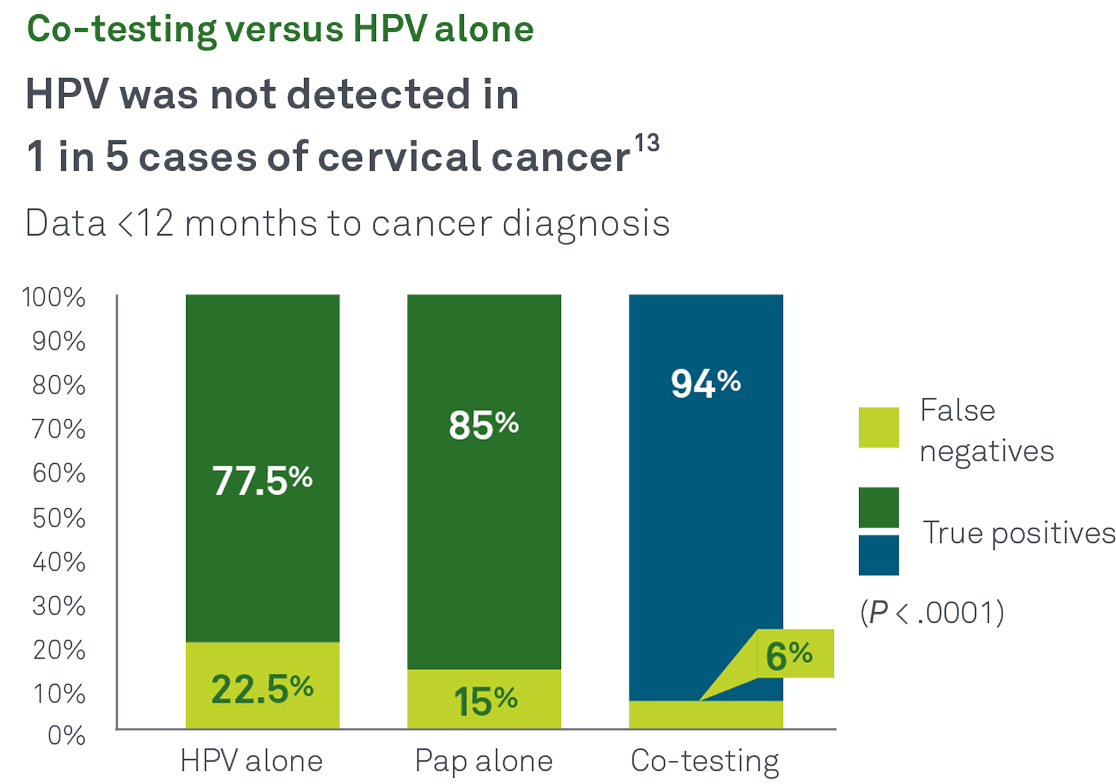

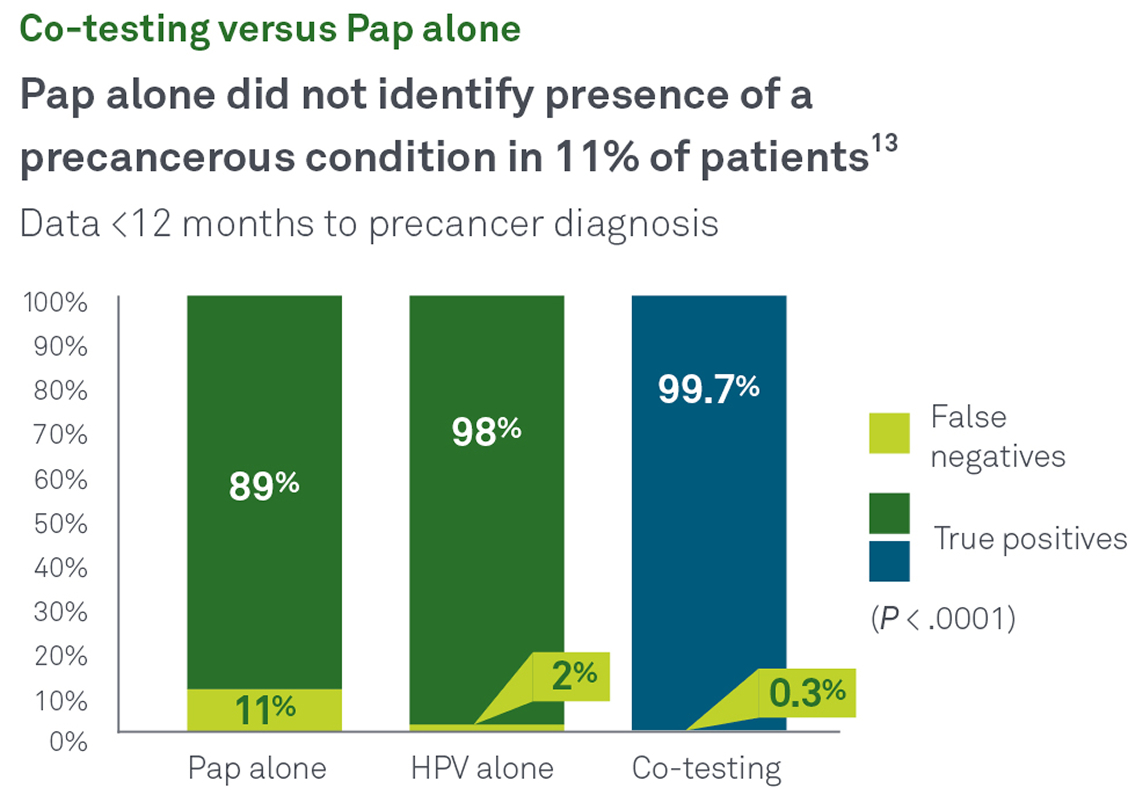

Co-testing with Pap and HPV together helps identify more cases of cancer and precancer than either test alone. In a recent Quest Diagnostics Health Trends® retrospective, longitudinal study:13

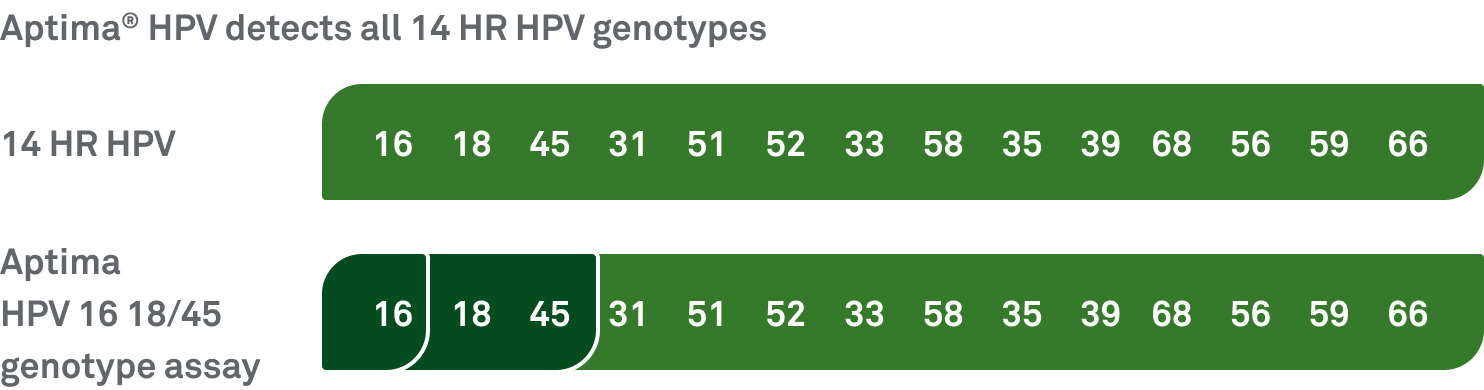

The Aptima mRNA HPV assay targets E6/E7 mRNA and identifies high risk infections that are both present and active, reducing the need for unnecessary patient call backs and overtreatment.

HPV types 16, 18, and 45 are associated with up to 80% of squamous cell carcinomas and up to 92% of HPV-related cervical adenocarcinomas.

Guidelines support co-testing

Guidelines from ACOG, USPSTF,* and ASCCP continue to endorse co-testing* as a Grade A–level screening option in women ages 30-65.8,10,12

*Endorses the 2018 USPSTF guidelines.

Smart codes from Quest make it easy to incorporate co-testing into your practice

Smart Codes help you order the combination of an image-guided Pap, HPV test, and sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing appropriate for your patient's age and risk factors.8,9,12

| TEST CODE | TEST NAME |

|---|---|

| 91384 |

Image-Guided Pap with Age-Based Screening Protocols |

| 91385 |

Image-Guided Pap with Age-Based Screening with CT/NG |

| 91386 |

Image-Guided Pap with Age-Based Screening with CT/NG, Trichomonas |

Components of panels can be ordered separately: ThinPrep Image-guided Pap (test code 58315); SurePath™ Imaging Pap (test code 18810); HPV mRNAE6/E7 (test code 90887); HPV Genotypes 16, 18/45 (test code 91826); Trichomonas vaginalis RNA, Qualitative, TMA, Pap Vial (test code 90521); Chlamydia trachomatis RNA, TMA, Urogenital (test code 11361); Neisseria gonorrhoeae RNA, TMA, Urogenital (test code 11362); Chlamydia/ Neisseria gonorrhoeae RNA, TMA, Urogenital (test code 11363).

Test codes may vary by location. Please contact your local laboratory for more information.

Primary HPV screening

With primary HPV screening, the hrHPV test is used as the primary method to assess cervical cancer risk, with the Pap test reserved for follow-up when the hrHPV test identifies potential concerns. With traditional co-testing, both tests are performed simultaneously.

The USPSTF recommends primary HPV screening in women 30-65 years old9

HPV patient self-collected

For some patients, self-collection provides a more discreet screening option. To meet the need for more flexibility, patients in any medical setting can privately collect the specimen using a vaginal swab.

- Identifies the same hrHPV genotypes specified in guidelines with similar confidence levels as physician-collected tests, while complying with all major screening guideline

- A vaginally collected specimen is insufficient for reflex to cytology as occurs with physician-administered HPV primary screening, so patients who receive positive or inconclusive results will still need to undergo traditional cervical collection and, in some cases, require colposcopy for further evaluation

Helping you deliver best-in-class screening and testing

Quest is committed to supporting you in providing the necessary testing for your patients.

Guideline-based solutions

Nationwide team of medical and scientific experts

Quanum® online lab services to simplify ordering

Financial assistance programs

In-network access with most private insurance plans, Medicare, and Medicaid

Supported by advanced esoteric testing labs

To access all testing options for cervical cancer screening, please visit our test directory

Test codes may vary by location. Please contact your local laboratory for more information.

References:

- NIH. Why are many women overdue for cervical cancer screening? February 22, 2022. Accessed December 23, 2024. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2022/overdue-cervical-cancer-screening-increasing

- Sabatino SA, Thompson TD, White MC, et al. Up-to-date breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening test use in the US, 2021. Prev Chronic Dis 2023;20:230071. doi:10.5888/pcd20.230071

- NIH. Cervical trends progress report. Cervical cancer screening. March 2024. Accessed December 20, 2024. https://progressreport.cancer.gov/detection/cervical_cancer

- Benard VB, Jackson JE, Greek A, et al. A population study of screening history and diagnostic outcomes of women with invasive cervical cancer. Cancer Med. 2021;10(12):4127-4137. doi:10.1002/cam4.3951

- Welsh HF, Andrus EC, Sandler CB, et al. Cervicovaginal and anal self-sampling for human papillomavirus testing in a transgender and gender diverse population assigned female at birth: comfort, difficulty, and willingness to use. LGBT Health. Published online April 4, 2024. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2023.0336

- Padela AI, Peek M, Johnson-Agbakwu CE, Hosseinian Z, Curlin F. Associations between religion-related factors and cervical cancer screening among Muslims in greater Chicago. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2014;18(4):326-32.doi:10.1097/LGT.0000000000000026

- Currier J, Madding R, Yanit K, Hedges M, Bruegl A. Cervical cancer screening: solutions for those who have experienced trauma. Gynecol Oncol. 2024;190(Suppl 1).

- ACOG. Updated cervical cancer screening guidelines. April 2021. Accessed December 20, 2024. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2021/04/updated-cervical-cancer-screening-guidelines

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement. Cervical cancer: Screening. August 21, 2018. Accessed December 20, 2024. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/cervical-cancer-screening

- American Cancer Society. The American Cancer Society guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. 2024. Accessed November 20, 2024. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/cervical-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/cervical-cancer-screening-guidelines.html

- NIH. Cervical cancer causes, risk factors, and prevention. Published online: August 2, 2024. Accessed December 20, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65901/

- ASCCP. Screening guidelines. 2020. Accessed July 1, 2022. https://www.asccp.org/screening-guidelines

- Kaufman HW, Alagia DP, Chen Z, et al. Contributions of liquid-based (Papanicolaou) cytology and human papillomavirus testing in cotesting for detection of cervical cancer and precancer in the United States. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;154(4):510-516. doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqaa074